Sampling Matters, and More About Wealth and Environmentalism

Because of the assumption that public attitudes and values about the environment are necessary preconditions for positive environmental change, scholars have also attempted to explain and predict individual environmental attitudes. Some work has shown the importance of local environmental and weather conditions for predicting environmental concern (Howe et al. 2012). This would suggest that individuals living in close proximity to environmental degradation and the consequences of environmental issues would be more concerned about the environment. On the other hand, some policymakers and scholars have relied on a “common sense” assumption that caring about the environment is a luxury afforded only to residents of wealthy nations (Dunlap & York 2008). They assume that individuals can’t care about the environment until their other needs are met, a version of the postmaterialism hypothesis. This is not fully supported by the literature, and I addressed a version of this question in an earlier blog post (https://amandamdewey.com/?p=83).

In a 2008 piece, Dunlap and York tested the postmaterialist explanation using results from 3 waves of the World Values Survey, correlating GDP per capita with measures of environmental concern.

For context, the World Values Survey is conducted through face-to-face interviews conducted by researchers in dozens of countries. Specific procedures vary but country, but each country has a sample size of at least 1000. Dunlap and York correlated national mean answers to environmental questions with GDP per capita from the World Bank. They also created additive indices for three categories of environmental variables: willingness to make economic sacrifices, green consumerism, and activism.

These survey questions are as follows:

- I am now going to read out some statements about the environment. For each one I read out, can you tell me whether you agree strongly, agree, disagree, or disagree strongly?

- I would agree to an increase in taxes if the extra money were used to prevent environmental damage.

- I would buy things at 20% higher than usual prices if it would help protect the environment.

- Here are two statements people sometimes make when discussing the environment and economic growth. Which of them comes closer to your own point of view?

- Protecting the environment should be given priority, even if it causes slower economic growth and some loss of jobs.

- Economic growth and creating jobs should be top priority, even if the environment suffers to some extent.

- Which, if any, of these things have you done in the last 12 months, out of concern for the environment?

- Have you chosen household products that you think are better for the environment?

- Have you decided for environmental reasons to reuse or recycle something rather than throw it away?

- Have you tried to reduce water consumption for environmental reasons?

- Have you attended a meeting or signed a letter or petition aimed at protecting the environment?

- Have you contributed to an environmental organization?

- I am going to name a number of organizations. For each one, could you tell me how much confidence you have in them: is it a great deal of confidence, quite a lot of confidence, not very much confidence or none at all?

- The Green/Ecology movement

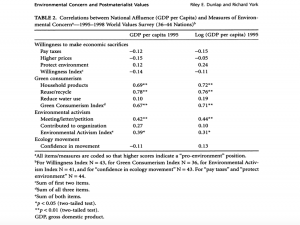

Dunlap and York find that national affluence and environmental concern do not correlate consistently and positively over time (Figure 1). Interestingly, respondents in low-income countries are actually more likely to be willing to sacrifice financially for the environment by some measures. These findings, if correct, suggest that environmentalism is not only a phenomenon reserved for the rich and that environmentalism in developing countries cannot be explained only by local environmental problems. The authors argue that environmentalism is globalizing and not purely affluence-based.

Figure 1: Dunlap and York’s Original Results

Table 2: Replication: Correlations between National Affluence (GDP per Capita) and Measures of Environmental Concern – 1995-1998 World Values Survey.

| GDP per capita 1995 | Log (GDP per capita) 1995 | |

| Willingness to make economic sacrifices | ||

| Pay taxes | -0.10 | -0.11 |

| Higher prices | -0.17 | -0.08 |

| Protect environment | 0.09 | 0.22 |

| Willingness Index | -0.14 | -0.10 |

| Green consumerism | ||

| Household products | 0.69** | 0.75** |

| Reuse/recycle | 0.78** | 0.78** |

| Reduce water use | 0.11 | 0.20 |

| Green Consumerism Index | 0.67** | 0.72** |

| Environmental activism | ||

| Meeting/letter/petition | 0.40* | 0.44** |

| Contributed to organization | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| Environmental Activism Index | 0.36* | 0.29 |

| Ecology movement | ||

| Confidence in movement | -0.12 | 0.11 |

Note: Missing Ghana and Brazil.

When I attempted to replicate Dunlap and York’s findings, I was very successful despite being unable to obtain data for two of the countries that they had included (Ghana and Brazil). My results were almost exactly the same, despite that complication (Table 2).

I, like the authors, found no statistically significant correlation between GDP per capita and any of the willingness to make economic sacrifices measures, including paying taxes, paying higher prices, prioritizing protecting the environment over economic growth, and the willingness index. In fact, several of these coefficients are negative. There are statistically significant positive correlations between GDP per capita and several of the green consumerism measures: household products, reusing and recycling, and green consumerism index. Unlike Dunlap and York, however, I did not find a statistically significant correlation between the activism index and the logarithm of GDP per capita. Overall, I would draw the same conclusions as the authors from the results of my replication. There are not consistent correlations between affluence and environmental concern and for the potentially strongest measures of concern, willingness to make economic sacrifices measures (Dunlap & York 2008), the coefficients are often negative.

I wanted to extend the project by comparing residents of urban and rural areas, with the idea that they might have different environmental perspectives, so I removed the 12 countries without those data (Table 3). However, I found that removing those countries and running the same analyses changes results. I then found that adding the Philippines back to the analysis brings the results close to the original replication (Table 4).

Table 3: Analysis removing the 12 countries without town-size data

| GDP per Capita 1995 | Log (GDP per capita) 1995 | |

| Willingness to make economic sacrifices | ||

| Pay taxes | -0.20 | -0.21 |

| Higher prices | -0.15 | -0.05 |

| Protect environment | 0.10 | 0.27 |

| Willingness Index | -0.19 | -0.14 |

| Green consumerism | ||

| Household products | 0.74** | 0.70** |

| Reuse/recycle | 0.83** | 0.72** |

| Reduce water use | 0.41* | 0.45* |

| Green Consumerism Index | 0.76** | 0.72** |

| Environmental activism | ||

| Meeting/letter/petition | 0.47* | 0.38* |

| Contributed to organization | 0.41* | 0.15 |

| Environmental activism index | 0.49** | 0.29 |

| Ecology movement | ||

| Confidence in movement | -0.30 | -0.17 |

Seeing the results change significantly based on changes to the included countries, this project then shifted to an exploration of the consequences of sampling choices.

Table 4: Replication removing 11 countries, added Philippines

| GDP per Capita 1995 | Log (GDP per capita) 1995 | |

| Willingness to make economic sacrifices | ||

| Pay taxes | -0.19 | -0.19 |

| Higher prices | -0.14 | -0.03 |

| Protect environment | 0.08 | 0.24 |

| Willingness Index | -0.17 | -0.12 |

| Green consumerism | ||

| Household products | 0.74** | 0.70** |

| Reuse/recycle | 0.83** | 0.71** |

| Reduce water use | 0.34 | 0.38* |

| Green Consumerism Index | 0.75** | 0.70** |

| Environmental activism | ||

| Meeting/letter/petition | 0.45* | 0.35 |

| Contributed to organization | 0.34 | 0.10 |

| Environmental activism index | 0.43* | 0.23 |

| Ecology movement | ||

| Confidence in movement | -0.32 | -0.20 |

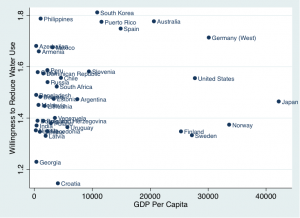

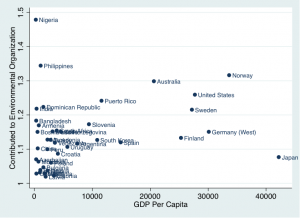

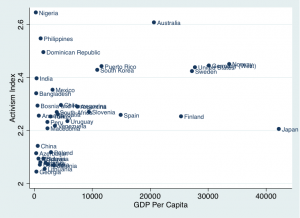

I examined the data for the twelve excluded countries to explore the reasons for the differences. To visualize how certain countries could affect results, the scatterplots below show the distribution of the countries’ average scores on a selection of variables: reducing water use (Figure 2), contributing to organizations (Figure 3), and the activism index (Figure 4). Many things stand out from these distributions. First, we see a wide distribution of scores among countries with the lowest GDPs per capita. This weakens the argument that GDP per capita is a valid predictor of environmental concern, as concern varies widely within similar GDP per capita levels. There are also several outliers, countries with very high scores and very low GDP per capita, that could alter the results. For example, it appears that the Philippines and Nigeria would both have strong effects on the results of these analyses, particularly with regard to the activism measures. With this in mind, what conclusions can we draw about the relationship between country-level wealth and country-level environmental concern?

Figure 2: Distribution of Willingness to Reduce Water Use

Note: Reduce water use variable ranges from 1 to 2.

Figure 3: Distribution of Contribution to Environmental Organization

Note: Environmental organization variable ranges from 1 to 2.

Figure 4: Distribution of Activism Index

Note: Activism index variable ranges from 2 to 4.

The central point here is that careful sampling is important, even when working at the level of the country. These results also show that while correlations of activism and green consumerism measures change with different samples, correlation of willingness to make economic sacrifices is not statistically significant in any sample. In fact, these coefficients are often negative. This is interesting and provides further evidence that not only is environmentalism not necessarily a luxury afforded to the rich or residents of wealthy nations, but in fact those who are more likely to be able to sacrifice for environmental protection are less likely to be willing to do it. Therefore, context and culture are important (Lee et al. 2015, Wolf & Moser 2011). While this and some of the other particular relationships between environmental measures and GDP are interesting and warrant future examination, this project raises the question: is it useful to make generalizations and predictions about and across countries? And how do we understand the relationship between wealth and environmentalism, at both the level of the individual and the level of the nation?

References

Dunlap, Riley E. and Richard York. 2008. “The Globalization of Environmental Concern and the Limits of the Post-Materialist Explanation: Evidence from Four Cross-National Surveys.” Sociological Quarterly 49:529-563.

Howe, P. D., Markowitz, E. M., Lee, T. M., Ko, C. Y., & Leiserowitz, A. (2013). Global perceptions of local temperature change. Nature Climate Change, 3(4), 352-356.

Lee, Tien Ming et al. 2015. “Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world.” Nature Climate Change. doi:10.1038/nclimate2728

Wolf, J. & Moser, S. C. Individual understandings, perceptions, and engagement with climate change: Insights from in-depth studies across the world. WIREs-Clim. Change 2, 547–569 (2011).